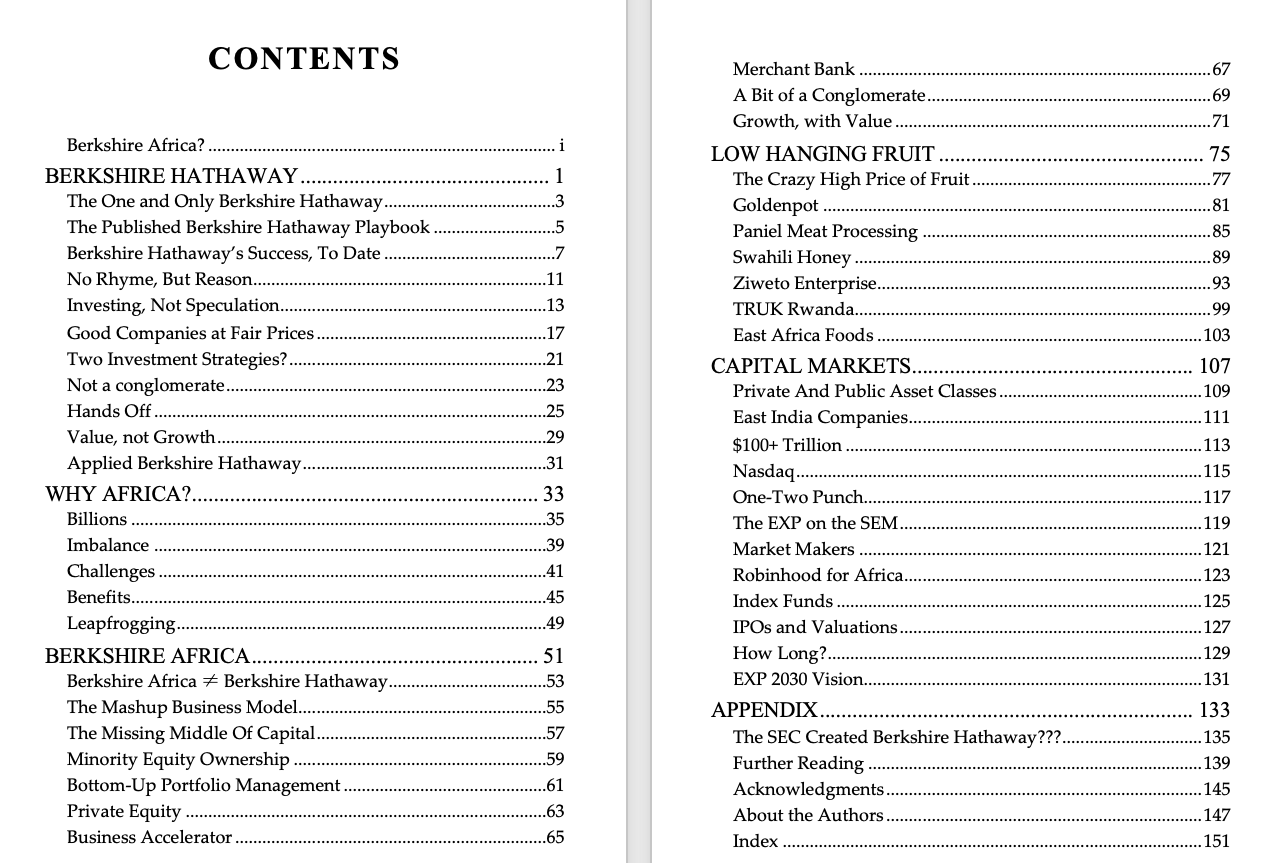

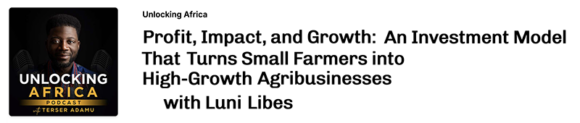

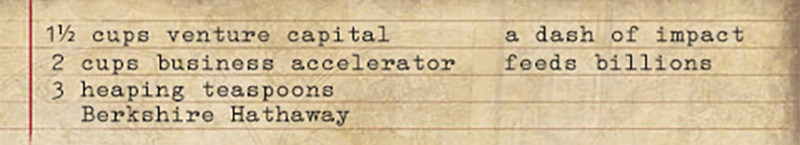

Luni and Jumaane, the co-founders of Africa Eats have published a book, “Berkshire Africa” that explains how our unique investment company has applied the learnings of venture capital, business accelerators, and Berkshire Hathaway toward solving hunger and poverty across Africa.

We’ve explained this before, in brief, but now have a 160-page book with far more details, including explaining the uniqueness of Berkshire Hathaway as one of the world’s largest public investment companies and how we’ve applied the lessons from their last 60 years of operations under the management of Warren Buffett.

The book is available on Amazon.com (or your local Amazon bookstore)

If you prefer more details than that “recipe” but less than a whole book, below is a shorter summary from the Q2 2024 investor update:

The Missing Middle of Capital

The fundamental financial bottleneck stifling the growth of SMEs across Sub-Saharan Africa is limited access to capital, commonly known in the economic development field as the “missing middle of capital.” Over the last four years operating Africa Eats, we have learned/learnt just how massively wide and deep is this gap of capital (where most often the gap, i.e., what is missing, exceeds the supply, i.e., what exists, by many multiples).

More specifically, in any given year there are millions of African entrepreneurs creating new companies and hundreds of thousands of SMEs with sufficient “traction” to raise funding, — if it were more freely available. Yet across Sub-Saharan Africa only 200-300 investment funds provide that funding, with each fund typically making fewer than 5 investments per year and typically do not invest every year. This is the most obvious of the capital gaps, but far from the only one.

Commercial banks rarely lend to these SMEs, even those that are funded by the investment funds (described in the previous paragraph). Likewise, SMEs that are growing 50%-100% annually with healthy profits also rarely get approved for bank loans. This is not unique to Africa. For example, without the Small Business Administration (SBA, a U.S. federal government agency) guaranteeing loans to SMEs, American commercial banks would not be lending to as many small businesses in America. The absence of an equivalently large SBA, across Sub-Saharan African countries, means SMEs are deemed too risky and lack the collateral requirements to give banks comfort to lend to them.

The next capital gap arises as the tens of thousands of succeeding companies keep growing. The old adage is, “it takes money to make money.” This is true for the medium-sized enterprises in multiple ways, from a growing need for operational capital, to additional asset finance for equipment, to hiring ahead of sales. The problem is the 200-300 investment funds tend to offer only one or just a couple vanilla finance products (e.g., term loans as debt, preferred shares as equity and the occasional mezzanine debt product), with just about none providing multiple forms of growth capital that fit all the various forms of SME capital needs. Thus, the next gap of capital is not completely absent, but successful companies have to spend another 9-24 months closing a second or third investment fund in order to have sufficient capital for a current need.

These three bottlenecks would be challenging enough, if at some scale this complexity would collapse down to working with one merchant bank or hiring an investment bank. It does not! Instead, as the hundreds of successful companies surpass $10 million in annual revenues the complexity grows. More specifically, most of the 200-300 investment funds cannot write checks big enough (or cannot write checks small enough if it is a $100+ million fund). Hence this growth capital is limited. Consequently, this finance gap reduces medium-sized enterprises ability to grow their tens of millions of dollars to reach the $100 million annual revenue milestone. Thus, yet another gap exists, solved only by creating syndicates of funders, slowing down the fundraising process even further if such complex fundraising efforts succeed at all.

The Berkshire Africa solution to this problem is quite simple in comparison. Be flexible! Provide a variety of investment capital, in a form that best fits the needs of the company, rather than focusing solely on just one investment structure or product. Write $10,000 checks when $10,000 is needed. Make $50,000-$500,000 working capital loans when operational capital is needed. Finance invoices. Lease trucks when trucks are needed. Match grants. This can be summarized as fill in whatever financial gaps arise.

Minority Equity Ownership

The Berkshire Africa business model takes the minority equity ownership model from venture capital funds. The core idea is to harness the power of entrepreneurs, investing in their companies rather than building companies from scratch within the investment company. Whether you believe entrepreneurs are born or can be taught, what is absolutely true is that no hired management is going to care as much about a company as its founder(s), who are typically willing to sacrifice everything to achieve their vision.

The investment model typically begins with minority equity investments into existing companies. Ideally companies that are already profitable. Ideally companies that are already growing 50%-200% year-over-year, or those that could be growing that quickly if only for sufficient investment capital. These investments are provided in check sizes that are lower than last year’s revenue. In summary, the Berkshire Africa model is to invest in entrepreneurs who against the odds are growing their revenues faster than the capital they deploy — i.e., in a capital efficient way.

Our investment model does not wait until the companies are already past $1 million in annual revenues. It does not pass up on these opportunities, but neither does it pass up on promising, profitable companies that earned just $20,000 in the last 12 months, where a $20,000 check could double or triple the size of the company.

Listen to the entrepreneurs! Let them determine the best use of funds. Question their plans even if their plans are sound, not only because markets are dynamic, but a good entrepreneur develops their ability to constantly question their past, current and future plans in-order to adapt quickly in dynamic markets. However, we ultimately let them do what they think is best. Far more often than not they know better than any investor what is needed to grow their business. Moreover, experience is often the training needed for the entrepreneur to manage a larger, fast-growing SME.

Expect many more opportunities to buy more equity as the company succeeds and use each of those moments to ask about lessons learned, ask about mistakes made, and ask about opportunities yet untapped. Our investment model of matching capital based on need affords the management team multiple and granular opportunities to engage our entrepreneurs as needed at an operational and management level across all aspects of their business.

Bottom-Up Portfolio Management

This bottom-up approach is reminiscent of the way Berkshire Hathaway lets its portfolio companies run with minimal input from HQ in Omaha. It is vastly different than the way traditional venture capital funds push their ideas top-down through formal board meetings and informal discussions with the founders. If the CEO is wise, he or she will ask for board-like advice when board-like advice is needed. If the investor is wise, he or she will be monitoring monthly or quarterly financial reports and monthly or quarterly investor updates, foreseeing common challenges before the CEO sees them through operations.

Investing is a partnership! Let the entrepreneurs and their management teams do what they do best, building companies and keeping their eyes open to curtail challenges and exploit opportunities. Let the investors do what investors do best, asking intelligent questions to help these entrepreneurs hone their plans, providing advice based on actual experience, and making connections between entrepreneurs to gather more advice and address on-the-ground realities.

At Africa Eats, the mantra at HQ is that we are a bottom-up culture. Listening to bizi has generated far more investment opportunity and growth than pushing ideas top-down from the HQ team to the bizi. This is a lesson we learned — as the HQ are all entrepreneurs — through trial, error, and adaptation, just like our entrepreneurs. This is how we became so flexible in our investment structures, listening to needs and being innovative to match those needs.

Listening is how we uncovered the huge opportunities in logistics. Listening is the main tool we are using to hone our plans of opening the capital markets to further fill the missing middle of capital (more on this later). Facilitated listening is what we do for most of the two days at our Annual Gathering.

Private Equity

How much to adopt from the play book of private equity funds is an ongoing debate in the Berkshire Africa business model. For example, if a founder/CEO of a relatively small and early growth-stage company is failing to meet his/her goals, should that CEO be pushed aside and replaced with management hired by the investment company?

A private equity (PE) fund would have long ago replaced that CEO with in-house management (although PE tends to focus on more mature companies). Meanwhile, a California-style venture capital fund would not hesitate to “shoot” the CEO and bring in a replacement. In the last 50 years at Berkshire Hathaway, the only CEOs the Omaha HQ have replaced are the two or three that were caught making unethical, if not fraudulent, decisions.

So far, Africa Eats has chosen to follow Berkshire Hathaway’s lead on that big question. Warren Buffett was forced to do otherwise a few times, and while he succeeded in those efforts, it was never something he wanted to do.

Likely there will come a time when Africa Eats does buy out a founder, but not yet.

Business Accelerator

All of the founder/CEOs of Africa Eats’ bizi have one thing in common, they are all learning on-the-job how to run companies of their current sizes, with their current challenges, having never done so previously.

If the companies were growing 10% per year, this would not be such a challenge, but on average the companies are growing 50% year-over-year, with some doubling and in any given year, at least one growing much faster.

What this means in reality (at the 100% compounded growth rate experienced by many of the bizi) is that an entrepreneur who has built the capacity to run a company earning $50,000 in annual revenues is, when succeeding, running a company earning $500,000 three and a half years later, then over $1 million two years after that. The systems used to run a company earning $50,000 in annual revenue are far simpler than the systems needed to run a $1+ million revenue company.

Most of the training in the Berkshire Africa model is devoted to what is commonly called a “business accelerator”. These CEOs do not have time to grow their companies at this speed while studying a formal MBA. Even if they did, few MBA programs teach lessons relevant to SMEs growing at this speed.

The annual in-person gathering is used not only to teach some of this material, but even more importantly, through CEOs networking and learning from each other, such that they trust each other to share challenges when they arise, getting solutions from fellow CEOs and fellow management rather than solely relying on Africa Eats’ HQ staff to provide those answers.

This is yet-another central piece of the bottom-up culture, where the answers to most challenges come bottom-up/side-to-side from fellow bizi rather than top-down from investors.

Merchant Bank

“Merchant banks” in the 21st century are not like those in the 19th century The closest equivalent to renown J.P. Morgan’s “House of Morgan” in modern times is Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

One major difference between these two entities is that Morgan innovated in investment structures and used his controlling interests in order to make the businesses more financially stable and profitable through corporate and financial restructuring. On the other hand, Berkshire nearly always simply purchased public equity, buying whole or parts of companies, with innovations in the rare cases, typically in troubled times, with a few preferred equity or debt bailouts.

Sub-Saharan Africa is missing the depth and breadth of financial institutions that 19th century New York City or for that matter 18th century London took for granted. The Berkshire Africa model aims to fill in the capital needs of its bizi from the first equity investment, through the various forms of growth capital, all the way to liquidity in the public stock markets. Furthermore, in future years, beyond the public listing, the Berkshire Africa model will likely build financial infrastructure to allow for factoring, corporate papers, corporate bonds, and agriculture futures, as examples.

In summary, as the bizi grow in scale their need for a greater variety of capital structures increases. Subsequently, there is a significant opportunity to re-implement, within Sub-Saharan Africa, the financial innovations of the 18th, 19th, 20th, and early 21st century which have become germane to global financial centers.

For the rest of the details, grab a copy of the book on Amazon.com.